Yoga, an old practice that blends the psyche, body, and soul, has become a worldwide peculiarity, contacting the existences of millions. However, behind the peaceful and adaptable stances, the controlled breath, and the thoughtful tranquility lies a significant way of thinking that has endured everyday hardship. At the core of this way of thinking is the sage Patanjali, frequently viewed as the “Father of Yoga.” Patanjali’s commitments to the yoga universe reach far beyond the actual stances and stretches. His fundamental work, the Yoga Sutras, fills in as the establishment for figuring out the embodiment of yoga as a profound, mental, and actual practice.

The existence of Patanjali

Patanjali’s life is covered in secrecy, and researchers banter about the specific course of events and personal subtleties. However, there is an overall agreement that he lived in India at some point between the second century BCE and the fourth century CE. Patanjali is frequently viewed as an incredible sage, researcher, and polymath. While his chips away at yoga have put him on the map, his impact has gone beyond the limits of this training.

Patanjali is likewise attributed with commitments to different fields, including sentence structure, Ayurveda (customary Indian medication), and theory. He is eminent for gathering the Mahabhashya, a thorough discourse on Panini’s language structure. This work made considerable commitments to the field of etymology.

His personality and the extent of his work have prompted different hypotheses, yet the Yoga Sutras have carved his name into the records of history.

The Yoga Sutras

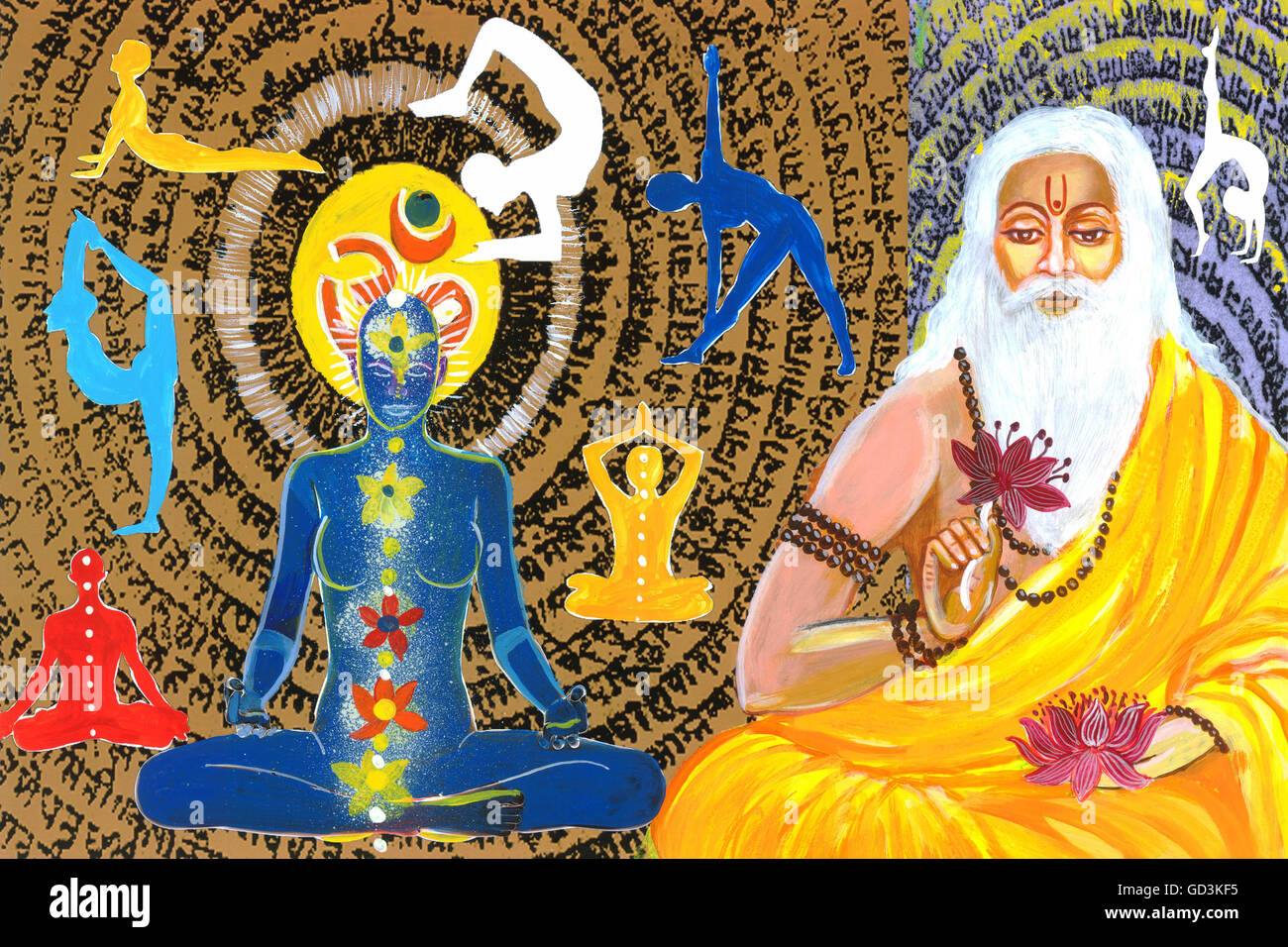

Patanjali’s most critical commitment to the world was the arrangement of the Yoga Sutras. This old text is an assortment of 196 truisms that act as a manual for the training and reasoning of yoga. The Yoga Sutras are frequently considered the fundamental text of old-style yoga and are partitioned into four sections, or “padas.”

Samadhi Pada (Fixation on Consideration): The primary section centers around the idea of the psyche and the various conditions of cognizance. Patanjali depicts the concept of “Samadhi,” the most noteworthy state of contemplation where the professional encounters total solidarity with the object of reflection.

Sadhana Pada (Practice): In this section, Patanjali directs the functional parts of yoga. He frames the eight appendages of yoga, known as Ashtanga Yoga, which incorporates moral standards (Yamas and Niyamas), actual stances (Asanas), breath control (Pranayama), and reflection.

Vibhuti Pada (Powers and Acknowledge): This segment examines the different enchanted encounters and otherworldly powers that can emerge from a committed yoga practice. Patanjali alerts us against getting occupied by these powers and stresses the significance of remaining fixed on a definitive objective of self-acknowledgment.

Kaivalya Pada (Opportunity): The last part explains the idea of “Kaivalya,” which is a definitive freedom or liberation from the pattern of birth and passing (Samsara). It investigates the concept of oneself and how to understand one’s fundamental essence.

The Yoga Sutras are written compactly and precisely, requiring translation and editing to be completely comprehended. Throughout the long term, various researchers and yogis have composed broad discourses on this work, making it more available to understudies and experts.

Patanjali’s Lessons and Theory

Patanjali’s way of thinking is well established in self-acknowledgment and the way to otherworldly arousal. His lessons revolve around yoga as an efficient and trained way to deal with accomplishing mental and profound immaculateness. Here are a few vital parts of Patanjali’s way of thinking:

The Eight Appendages of Yoga (Ashtanga Yoga): Patanjali’s Ashtanga Yoga guides an all-encompassing and coordinated way to deal with yoga. It includes actual stances and breath control, as well as morals and moral rules. This eightfold way directs professionals toward profound advancement and self-acknowledgment.

Yamas and Niyamas: The Yamas are moral rules that envelop peacefulness, honesty, non-taking, celibacy, and non-possessiveness. The Niyamas, then again, incorporate tidiness, satisfaction, severity, self-study, and giving up to a higher power. These standards are an ethical compass for yogis to follow a high-minded and healthy lifestyle.

The Nature of the Psyche: Patanjali’s investigation of the brain is essential to his thinking. He recognizes the vacillations of the brain (vrittis) as the primary driver of affliction and interruptions. Yoga expects to quiet these variances, prompting a more precise and peaceful condition of cognizance.

Samadhi: Patanjali depicts Samadhi as the condition of contemplation where the expert encounters unity with the object of reflection. This is the definitive objective of yoga, where the singular self converges with the all-inclusive self.

Patanjali’s lessons are not restricted to the actual stances of yoga. All things being equal, they give a thorough manual for living a significant, adjusted, and profoundly mindful life.

Patanjali’s Getting Through Heritage

Patanjali’s effect on the universe of yoga couldn’t be more significant. His Yoga Sutras have served as the foundation for yoga reasoning and practice for more than two centuries. Indeed, even in the cutting-edge world, where yoga has changed into a worldwide wellness and well-being pattern, the center standards set near Patanjali stay significant.

Yoga as a Comprehensive Practice: Patanjali’s accentuation on the all-encompassing nature of yoga, consolidating physical, mental, and otherworldly aspects, is currently at the core of yoga today. While many might begin with actual stances (Asanas), they frequently find significant mental and profound advantages as they dive further into their training.

Moral and Moral Rules: The Yamas and Niyamas keep on directing experts toward having an ethical and adjusted existence. They act as a wake-up call that yoga isn’t just about actual ability but also about moral living and internal development.

Mindfulness and Contemplation: Patanjali’s lessons on controlling the variances of the psyche through reflection and breath control (Pranayama) have earned respect for emotional well-being and stress management. Methods learned from Patanjali’s work are utilized in care rehearsals all over the planet.

Eight Appendages of Yoga: The Ashtanga Yoga framework illustrated by Patanjali has been embraced and adjusted by incalculable yoga schools and instructors. It gives an organized and deliberate way to deal with yoga, guaranteeing that it remains a balanced practice.

Final Words: Father of Yoga

Patanjali, the Father of Yoga, remains a respected figure in yoga and reasoning. His significant bits of knowledge about the human brain, morals, and the way to self-acknowledgment have left a permanent imprint on the act of yoga. As yoga proceeds to develop and extend its reach across the globe, the getting-through tradition of Patanjali is an update that yoga isn’t just about actual stances; it is a significant study of self-disclosure and self-improvement. Patanjali’s immortal insight welcomes us to investigate the profundities of our own cognizance, embrace an existence of equilibrium and righteousness, and encounter the extraordinary force of yoga in its aspects.

Faqs: Father of Yoga

Who is Patanjali, and why would he say he is known as the Father of Yoga?

Patanjali is an incredible sage who is frequently referred to as the Father of Yoga. He is famous for gathering the Yoga Sutras, an old text that fills in the fundamental way of yoga thinking. His work efficiently frames the standards and practices of yoga, making it available and far-reaching for yearning yogis. His lessons lastingly affect the universe of yoga, earning him the title of the Father of Yoga.

When did Patanjali live, and with whom are we familiar?

The specific course of events in Patanjali’s life is discussed among researchers. Yet, it is, for the most part, accepted that he lived in India between the second century BCE and the fourth century CE. Regardless of his essential job throughout yoga, he has yet to be aware of his life. He is attributed with commitments to different fields, including syntax, Ayurveda, and reasoning, notwithstanding his work on yoga.

What is Patanjali’s most renowned work, and why is it critical in yoga?

Patanjali’s most well-known work is the Yoga Sutras. This text is critical because it fills in as a complete manual for thinking and practicing yoga. The Yoga Sutras are isolated into four sections, with every part zeroing in on various aspects of yoga, including moral standards, actual stances, breath control, and reflection. It has become the central text for figuring out traditional yoga and has affected incalculable yogis and professionals throughout the long term.